Frequently Asked Question

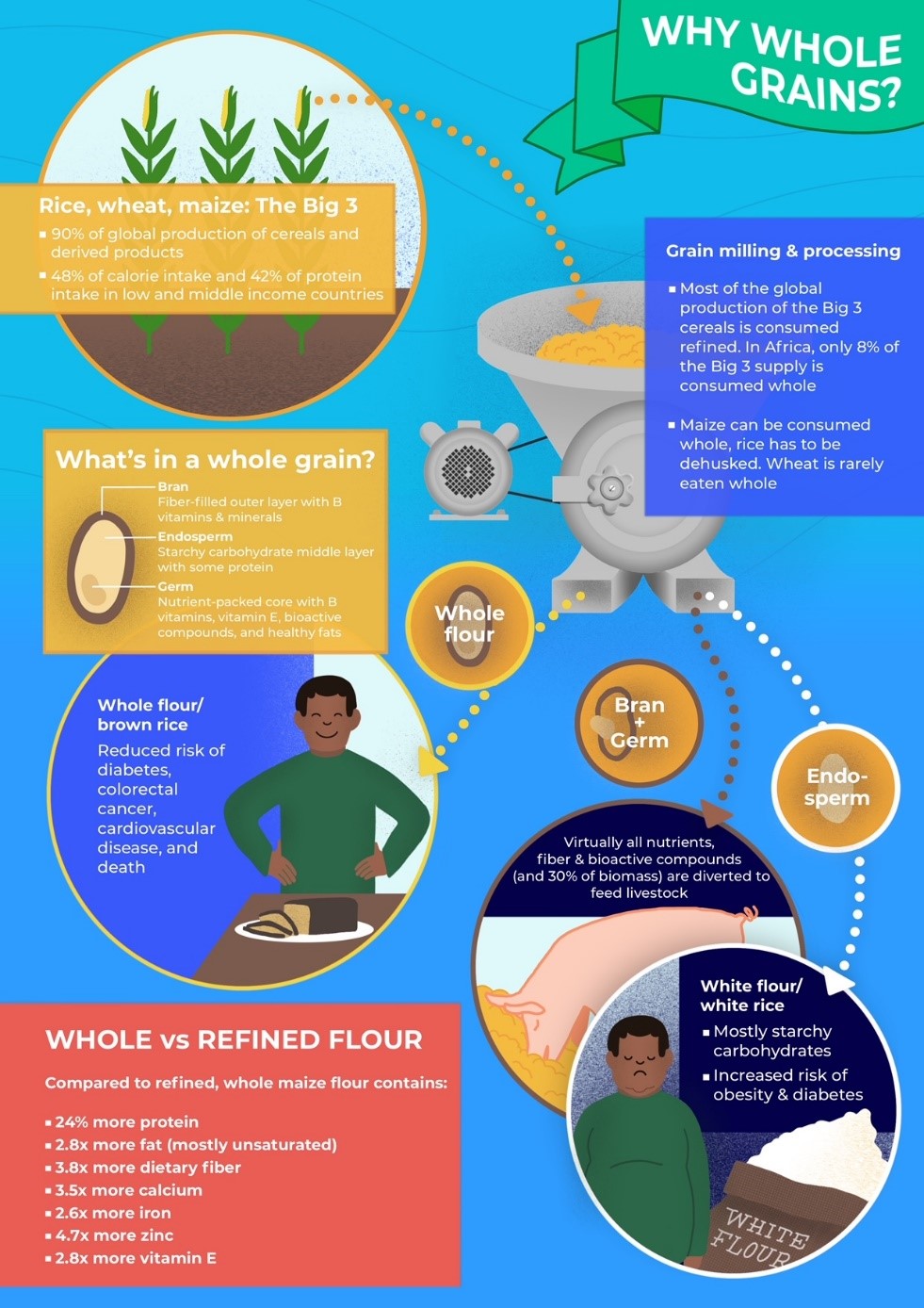

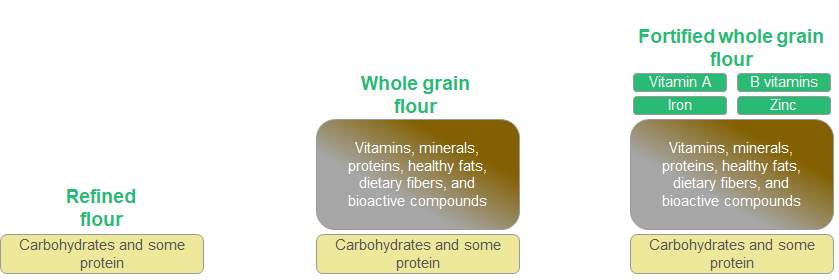

Most school meals in sub-sahara Africa serve a maize meal commonly known as ugali/posho/kaunga that is made from refined maize flour as a major component. Refined flour is rich in carbohydrates, but poor in nutrients as virtually all the proteins, healthy fats, vitamins, minerals, fibers, and bioactive compounds naturally present in the maize grain are removed in the refined milling process. Milling the whole grain preserves all these nutrients in the flour, and fortifying this whole grain flour with additional vitamins and minerals produces a highly nutritious food: fortified whole grain (FWG) flour, as illustrated below.

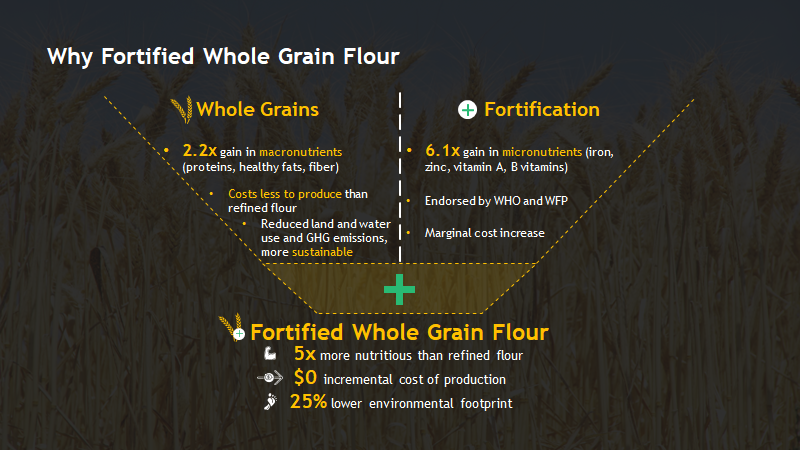

Shifting school meals from refined grain flour to FWG flour can make school meals much more nutritious, at no additional cost to schools. Across a range of macro and micronutrients, FWG maize flour is five times more nutritious than refined flour. With kaunga typically representing at least half of a school meal plate, shifting to FWG can make meals substantially more nutrient-dense in a budget-neutral way.

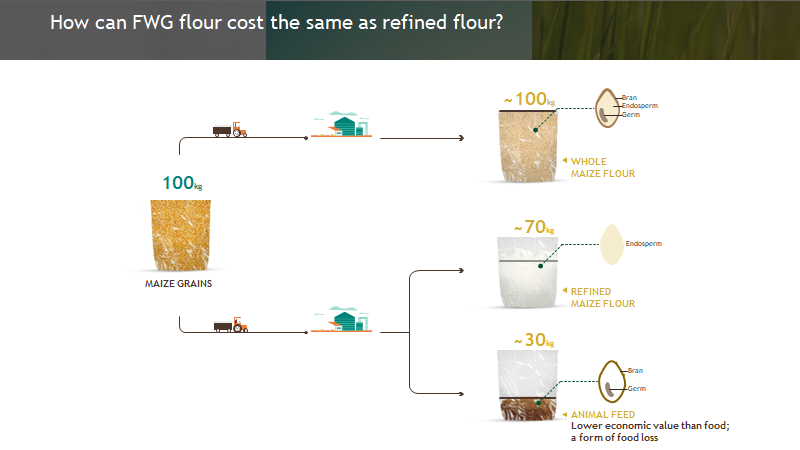

From 100 kg of maize grain, mills extract about 70 kg of refined flour, with the remainder (the nutritious part of the grain) being sold at a much lower price to produce animal feed. From the same 100 kg of grain, mills can produce almost 100 kg of whole grain flour, sold at food price. Because the major cost (~80%) in producing flour is the cost of grains, producing 1 kg of whole flour, which requires 20-30% less grain, costs less than producing 1 kg of refined flour. This gain in production cost can be used to absorb the incremental cost of fortification, enabling millers to supply FWG flour at the same cost as refined flour.

Yes. A True Value of Food analysis conducted by McKinsey & Co. on the impact of shifting all consumption of flour in school feeding to FWG in Rwanda showed an estimated annual benefit to the country of USD 50M+ given the positive health, environmental, and economic impacts.

Yes. FWG flour in school feeding is actually a “Made in Rwanda” innovation. Starting in October 2021, nearly 14,000 students in 18 schools in Nyaruguru and Nyamagabe are being served FWG kaunga, at no additional cost to the schools. An evaluation conducted in December showed that 73% of the children were aware of the nutritional advantages of FWG and 97% of P6 children preferred FWG kaunga over its refined version. Since then, FWG has been continuously expanded, in partnership with the World Food Programme, to 74,000 schoolchildren in 81 schools, with additional schools planned. FWG has also been included in MINEDUC’s school feeding guidelines. In Burundi, 180,000 students are being served FWG, and about 60,000 in Kenya.

A strong public-private partnership, starting with school feeding. On the public side, the National School Feeding Program needs to switch all maize flour procurement to FWG flour (budget-neutrally) to provide the structured demand to enable investment by factories (millers). Sensitizing the school community about the benefits of FWG and other nutritious foods is also key. On the private side, millers need to supply high-quality FWG compliant with food safety and fortification standards at the same price as refined flour. This will require investment in new machinery to efficiently produce FWG and engagement of local farmers and aggregators to improve quality throughout the value chain.